Since I just posted a story dealing with Maine’s Indians, let’s keep the theme going with this story written in September of 1975. I found this clip in the Brownsville (Texas) HERALD.

By ARTHUR FREDERICK

ALTON, Maine (UPI) – The Indians camped next to the Pushaw Stream because the fishing was good. And they stayed for thousands of years.

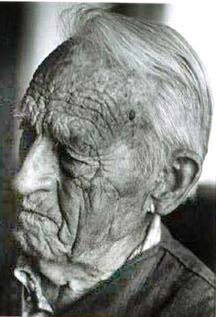

A University of Maine anthropology professor, a group of associates and students spent the summer scraping away the dirt covering the campsite and learned a lot about the Indians who lived along the stream starting about 7,000 years ago.

Prof. Dave Sanger said the Indians who lived here were not the forebears of the Indian tribes who now live in Maine.

“In my opinion these people were not the ancestors of the modern Indians, such as the Penobscots,” he said.

Sanger said work at the campsite has shown that different groups lived in the area during the years.

“They came in at a time when the forests in Maine were changing their character. I think they were following the forest type they were accustomed to from the St. Lawrence Drainage area,” he said. “They stayed here until about 3,000 years ago and then all traces disappear and they seem to be replaced immediately with different tools and burial techniques.”

The Indians who lived along the Pushaw spent at least part of the year along the coast fishing and harvesting shellfish. But Sanger thinks it took them some years to learn to take advantage of the sea.

“It may be that some of the earlier people were not adapted to this coastal interim migration pattern,” he said. “I think we are getting evidence of some of the very earliest people who came into Maine not being tuned in to the marine resources. I have a suspicion that the first of these people may not have been fully aware of the potential of the Gulf of Maine.”

“These people made use of inland resources. There was good fishing. They also went to sea on occasion.”

Perhaps the best aspect of the dig site is that it has never been disturbed. Sanger said there used to be many potential dig sites in Maine, but most of them have been destroyed through construction or farming. Many of those left have been dug by amateurs. Sanger’s site is on private property and has never been dug before.

“It’s a big site and it contains several components, each representing different people at different times,” he said. “The first starts about 7,000 years ago and is right down on the glacial till. Then we come up to about 4,000 or 5,000 years ago, the so-called Red Paint people, and then 3,000 years ago we have the Susquehanna. That goes to 2,000 years ago and then we have a break.”

The site was found about five years ago and Sanger said work has been conducted slowly ever since. He estimated only about 15 percent of the site has been dug.