Author Archives: Bill Frederick

Magazine writing: My barn-find Harley

When I found this old Harley-Davidson in a barn, I thought it would make a great story for one of the motorcycle magazines. I wrote this story and shipped it off and was surprised when it was rejected. I sent it to a couple of other magazines and they rejected it, too. I soon figured out why: Motorcycle magazines love “before and after” stories. They want to see the old unrestored bike, and then they want to see the bike all done over and like-new. I thought the fact the bike was still in the barn somewhere was interesting, but I guess the editors didn’t agree. The lesson: Stick to the formula, no matter how tired and hackneyed it may be.

Editors note: I just found an old photo of the bike, which I have inserted (12/01/2014).

I found it in a barn

By BILL FREDERICK

You’ve seen it a million times. You page through your favorite motorcycle magazine and come to a dazzling spread on a beautiful antique Harley, restored and polished to perfection. The story always says something like:

“This fine-looking 1948 Panhead has been carefully restored to better-than-new condition. Before the restoration, the only thing left of the original was a valve stem cap and a half-pint of gear oil.”

And then comes the worst part:

“The Panhead was found in an old barn.”

There are a lot of old barns in New England and I’ve looked through plenty of them, but I’ve never found an old motorcycle. Never an Indian, never an old Knucklehead, never even some interesting old parts. Nothing.

Nothing, that is, until two summers ago.

I was at a party at a house out in the country, about 50 miles from home. I was making small talk with the host, standing around in the front yard, when he brought up my favorite subject.

I was at a party at a house out in the country, about 50 miles from home. I was making small talk with the host, standing around in the front yard, when he brought up my favorite subject.

“You’ve got a Harley, right?” he asked. Then he nodded toward the barn that was hidden behind some pines a hundred yards away. “You know, I’m glad you’re here, because you might be able to tell me what I got out there in the barn.”

Oh, boy, I thought, maybe this is the big one. An old Harley, buried up to its passing lights in hay, complete and waiting for a little polish and some fresh gas. It was hard to keep from running ahead of the guy, but I wanted to act nonchalant.

It was dark in the barn and it took a bit for my eyes to adjust.

“It’s over here,” the guy said, squeezing himself past an old pickup that was parked near the door.

Memorial Day

Bay Pines VA Center, St. Petersburg

Hari Krishna parade

St. Augustine, FL

Journalism as history II — the Phoenicians in Maine

Earlier I posted a story I wrote about some ancient amphoras (jugs) that were found by divers on the sea floor off Maine. That story included some expert opinions that the amphoras came from ancient Phoenicians who had visited the Maine coast before the birth of Christ. Now, my rummaging around in my old files has turned up a second story I wrote in 1976 that claimed the stone etchings on Monhegan Island (and perhaps elsewhere) also had connections to the Phoenicians. I don’t recall the origins of either of these stories, so I don’t know if they came from the same source. But both of the stories were well played in newspapers around the country.

By ARTHUR FREDERICK

MONHEGAN ISLAND, Maine (UPI) – A few crude rock carvings on this craggy coastal island could force historians to take another look at who discovered America and where the American Indians came from.

The carvings, known as the Monhegan Inscription, have been studied since 1855. But they and other carvings in New England have taken on new meaning to archeologists and linguists in the past few years. And they may indicate that the New England coast was a busy trade center for Phoenician sailors as long ago as 200 B.C.

For many years the inscriptions along with inscriptions in Bourne, Mass. and elsewhere in the region have been thought to be the work of Norse sailors. The theory was that the Norsemen discovered America several hundred years before Columbus.

But now some archeologists, including James P. Whittall, director of archeology for the Early Sites Research Society in Boston, feel the inscription is written in Ogam script used by the Celts in the Iberian peninsula as long ago as 2000 B.C.

Whittall said the inscription was translated by Dr. Barry Fell, president of Boston’s Epigraphic Society, to read “Long ships of Phoenicia: cargo lots landing quay.” If the translation is correct, it could have been a message to Phoenicians who may have landed at Monhegan long before the birth of Christ to deal in fish, furs and minerals.

“When these inscriptions were found along the New England coast, some tried to apply them to the Norsemen because some of the symbols are the same,” Whittall said. “They forced the symbols into a Norse translation, so scholars ended up calling them a fraud.”

“They never studied Iberian script, because it then was very little known and not translated,” he said. “One of the problems with the Norse is there is a close similarity between Iberian and Norse runic script, and we feel runic script was developed out of Iberian script.”

Nick Apollonio’s guitars

I don’t remember writing this story in 1974. I don’t remember meeting Nick Apollonio, and I don’t know if I went down to Camden to interview him or if I simply talked to him on the telephone. But I did look him up via Google and it seems that he’s still in the Camden area and still making guitars that musicians value very highly. He was 27 when I wrote this story, and that would make him 67 now – my age. As I’ve noted elsewhere on this blog, Maine was an absolute treasure trove of interesting people doing great things. Kind of a writer’s paradise.

Camden man is specialist in guitars

CAMDEN, Maine (UPI) – The guitars that Nick Apollonio makes are fashioned out of redwood or cedar on the second floor of a barn that overlooks the rocky coast.

The six and 12-string instruments have been coming out of Apollonio’s shop, one at a time, since 1968. He says they are about the best that can be found anywhere.

“I specialize in 12-strings, because I found I could make a good tone,” he said. But Apollonio also makes six-string guitars, dulcimers, and he recently completed his first fiddle.

“I did a fiddle last February, and that was great,” he said. “I used a redwood top with a walnut body, and it sounds excellent.” Violins are usually made out of maple, with spruce tops.

Apollonio is 27, and the guitar shop, which he calls The Works, got underway in 1968, right after he got out of college.

“I got into it slowly,” he said. “When I was a teenager, I learned to play the electric guitar and later on developed an interest in folk music, to the point where I wanted my own guitar.

“A friend of mine, Gordon Bok, had two excellent guitars, one of which he had made, and he convinced me that I should try to make one,” he said. “It was so simple that I thought it was worth a try.”

The first two or three guitars came out sounding pretty good.

“Somebody gave me an order, and a little later on I just went ahead and opened the shop. I sold about 12 instruments that first summer,” he said.

One of Apollonio’s instruments was made for Paul Stookey, formerly with the Peter Paul and Mary group.

The guitars can be made to produce different tones and the finish can be simple or elaborate. The instruments cost anywhere from $100 to $700.

“The difference is tone, playability and the detail that goes into it,” he said.

Most of the orders have resulted from word of mouth and most come from the New England area, although Apollonio has received orders from as far away as California and Louisiana.

Apollonio says he wants to get into making stringed instruments which are played in the Balkans.

“The Ukranians and the Greeks use all kinds of little stringed instruments for their dances, and I’m curious about them,” he said.

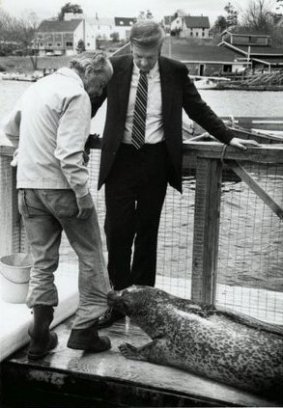

Animal stories/Rockport Harbor II

While Andre the Seal held the title of most-written-about animal in Rockport Harbor, there were other animal stories that occasionally originated in that seacoast town. This story was about a baby sperm whale that floated into the harbor, and the efforts to keep it alive. I don’t recall the outcome of this story, whether the baby whale lived or died.

By ARTHUR FREDERICK

ROCKPORT, Maine (UPI) – They built a sling out of beams and fish nets, and gently eased the newborn sperm whale over it in the shallow water near the shore at Rockport Harbor.

Straps that usually hoist boats from the water were drawn up and the baby whale, weak from hunger and close to death, was moved onto a dock and into the back of a large red and white van for the ride down the turnpike to Boston.

The little whale had floated into the harbor early Monday. At first it swam in lazy circles. Then it floated up and rested on the sand near shore.

People waded out and tried to push the whale back into deep water, but it kept turning about and moving back near the shore. Hundreds of people lined the beach and watched the whale as it lay in the shallow water.

Biology students from the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor came to Rockport and helped experts from the New England Aquarium in Boston check over the whale. At first it was thought eh animal was about a year old, but Dr. Joseph Geraci, a veterinarian at the New England Aquarium, and aquarium director John Prescott said the whale was a baby which had been separated from or rejected by its mother,,

They said the baby whale hadn’t been fed in some time. They said it was dehydrated and had lost as much as a third of its weight, which at birth is about 3,000 pounds.

A private plane was sent aloft to search the coast for the mother. If she had been found, the baby would have been towed out to meet her. But she wasn’t found, and Prescott and Dr. Geraci began making plans to move the whale to the New York Aquarium.

The examination early Tuesday, however, indicated the whale wouldn’t survive the trip. It was decided to take it to the aquarium in Boston.

Harry Goodridge, the local harbormaster, had been with the whale since it first came into the harbor.

“They gave him massive doses of antibiotics,” Goodridge said. “There is a lot of interest in him because he’s the first live sperm whale anyone’s ever had.”

Louis Garibaldi, the New England Aquarium’s curator, cautioned that chances of saving the little whale were slim.

“The animal is in very poor condition,” he said. “It is a recent newborn, it’s very thin and it’s had little nutrition.”

“The prognosis is poor, and it appears the whale may die no matter what we do.”

Animal stories: Andre the Seal

There are some stories that get written once a year, over and over again. In Maine, the king of all once-a-year stories was Andre the Seal. Maine reporters cringed every year when Andre, a harbor seal that had been abandoned as a baby by his mother, would return to Rockport Harbor. I must have written this story at least a half-dozen times. This was the 1976 version.

Andre returns to Maine

By ARTHUR FREDERICK

ROCKPORT, Maine (UPI) – When the sky lightened over a foggy Rockport Harbor Monday, Andre was there.

Andre, a fat 16-year-old harbor seal, had spent most of the past two weeks lounging in a series of rowboats from Port Clyde to Cape Rosier. His trainer, Harry Goodridge, Rockport’s harbormaster, was beginning to think that Andre had decided to stay free.

Goodridge found Andre when he was a small pup, not long after the seal had been abandoned by his mother. Goodridge kept the little seal in his bathtub for a while, and later built him a pen in the harbor.

Goodridge found Andre when he was a small pup, not long after the seal had been abandoned by his mother. Goodridge kept the little seal in his bathtub for a while, and later built him a pen in the harbor.

Andre learned tricks, and the seal and his trainer have been entertaining visitors to Rockport since the early 1960s.

In the winter, Andre would swim south, and spent some time in the harbor in Marblehead, Mass. But the past three years Goodridge has taken Andrew to the New England Aquarium in Boston for the winter.

In the spring, Andre has been taken to Marblehead and set free. A few days later, he shows up in Rockport.

Andre usually makes the swim in three or four days. But this year was different.

Andre visited some people along the coast and played games with boaters before arriving in Port Clyde, a few miles south of Rockport. He climbed into a rowboat, moored 200 feet offshore, and went to sleep.

Andre stayed in the boat for two days, sleeping and sunning himself. A local resident said the seal would occasionally scoop up a flipperful of water from the bottom of the boat and lazily splash himself. His next visit was at Deer Isle, about 20 miles east of Rockport. He spent some time in a rowboat there, and then was spotted in a boat in Cape Rozier.

But two boys were at Goodridge’s house early Monday.

“They told me he was back,” Goodridge said. “I went down to the harbor and and he was there heckling a lobsterman.”

“When he saw me, he jumped riight into his cage.”

Goodridge said Andre looked good, and said he had lost some of the weight he had gained over the winter at the aquarium.

“He was just enjoying his vacation, I guess,” Goodridge said. “I began to get a little worried when he didn’t come home, but I kept thinking that he was free for years, and that he always came back.”

When Andre spent his winters free, he would sometimes take off for extended periods.

“He was gone for more than three months once,” Goodridge said. “Probably went to the North Pole.”

While Goodridge and his wife worry about Andre when he’s gone, they both have hoped that the seal would one day leave Rockport Harbor and learn to live on his own.

“We’ve always hoped he would go wild,” Mrs. Goodridge said. “We hate to keep him cooped up all year.”

“But if he comes back, There’s a place for him, and plenty of fish.”

Bike shop, Wheels Through Time Museum

Tale of the Cobra

This is another example of stories that sort of fall in one’s lap. A small group of us were riding some mountain roads in Tennessee and North Carolina last fall and we pulled into a rest area on the Cherohala Skyway. We were only there a few minutes when a beautiful silver Cobra pulled in and parked. We talked to the man and woman who got out of the car, and this is the story that resulted.

Before we got to the Tail of the Dragon last weekend, we spent some quality time on the Cherohala Skyway, which winds its way through almost 40 miles of Tennessee and North Carolina back country.

At one point, Scott led us off the road and onto a scenic overlook, where we spent a little time taking pictures. While we were there, a really beautiful silver Cobra came in and parked near us. A middle-aged couple got out.

The woman headed for the rest room, and Scott approached the man and asked him about the car, specifically whether it was an original Cobra or a reproduction. The man said it was built from a kit.

“I don’t own it, but I helped build it,” the man said. “It belongs to the lady.”

The fellow went on to tell us that the woman’s husband had purchased the kit, but he soon was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease and had to stop the construction project before it had really begun.

“I was a friend of his,” the man said. “When Don got sick, 40 friends got together and we all pitched in and finished the car.”

The car was completed in 2009. The owner, Don “Vorcy” Voorhis, got a chance to drive it. He died just three months after it was completed.

The car was completed in 2009. The owner, Don “Vorcy” Voorhis, got a chance to drive it. He died just three months after it was completed.

The driver said that the woman, Cheryl Voorhis, didn’t drive the car, but every once in a while she liked to take a ride in it, so he would go over and they would get the car out of the garage and take it for a spin.

A beautiful car, and a beautiful story.

If you would like to see a step-by-step report on the build process for this car, visit: